Been quite some time since I’ve done anything with this blog. I’m still working on films, screenplays and learning Adobe CS6. I’m also pretty active in local, state, and national politics so I guess I’m wondering what I want this blog to be about – entertainment, politics or both. Is that even possible?

Photoshop Portfolio

Photoshop Portfolio

(or My First Experiments)

This is a collection of the work I have been doing in Adobe Photoshop CS6 for my first semester back at IUPUI. This will also be the last blog update until the new site is up and running, so for the 2 or 3 of you who have been following this blog it shouldn’t be a difficult move….especially if one of you has a truck I can borrow.

Without further delay –

This fine fellow is one I like to call the “Boggy Monster.” The original photo was the trunk of a tree I saw at Anderson Falls.

In the original I was trying to make the monster look all natural, with a leafy mustache, but I didn’t like the way it turned out. I think I am better at using layer masks anyway, so I found a cool beard online and blended it in using a layer mask and the healing brush to blur the edges.

This is Tammy Jo, the “Party Animal.” I am working on an idea for a 3 panel comic strip called “The Youth Group.” I guess the idea is sort of like Monster High, but set in a church youth group with adult themes. Tammy Jo is the first character design (unless you count Stainglass Jesus -hehe). She was created primarily using shapes in Photoshop. For the portfolio assignment we had to create an image based on an adjective of our choosing, so I chose this “party animal.”

Clutch is my favorite band (next to Pearl Jam and Faith No More) and one of my favorite songs is “Rock-n-Roll Outlaw.” I originally wanted to do a paint brushed/Clint Eastwood style image, a lot less cartoony, but I was pressed for time (and you’ll understand when you see some of the other images). The flying V guitar image was snagged from ProductWiki without permission.

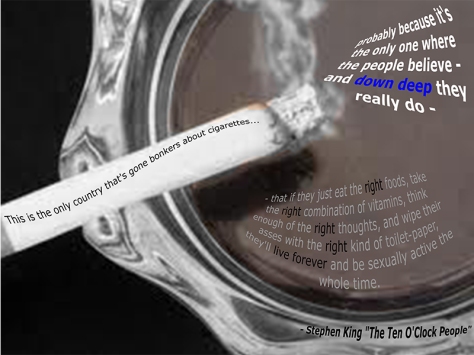

This was an exercise in typography. Stephen King is my all time favorite author and “The Ten O’Clock People” is one of my favorite short stories primarily because of this single paragraph quote. I quit smoking over two years ago. I’ve been able to pick the habit up and put it down with relative ease, but I know it’s a hard addiction. However, I also know that life is 100% fatal and regardless of your faith there is no magic cocktail for immortality. I used levels on the image then a layer mask to bring back the color in the center of the ashtray. The rest was merely curving the type.

Halloween is my Christmas. It was the first holiday I remember celebrating. I don’t go all out like I’d like, but this year I dressed up in a chemical suit (thanks baby) and put on some zombie make-up after I carved this jack-o-lantern (note: next year I have to help the kids carve theirs first). For this image I simply adjusted the levels. I played around with some other blend modes, but none of them had this effect. “No words” to describe this image.

This is another image made completely in Photoshop and is part of “The Youth Group” comic strip I am working on. These are the first images of Stain Glass Jesus, Big Daddy Jesus and Suffering Jesus.

The first image is based on the photograph below. I was trying to work with content aware fill and the healing brush. Not sure if I like how it came out, but that is the extent of my skill thus far.

Black is my favorite color. I love the sight of big, bold black ink on a white page. I’m not as morose as this character, the typical goth I guess, but black – the absence of color (like the blank page) – represents me, always waiting to be filled.

I used to write for a LOST fan site, that’s how much I love that show. I never done that before, nor have I done it since. The show changed the way I saw film and television and what it could do. Terry O’Quinn is one of my favorite actors, despite the poor shows he’s been cast (666 Park Avenue?). This image from the show stuck out for me because it summed up his character, completely misunderstood.

One day I was goofing off at home and took a photo of two of my wife’s figures arm and arm. This is their second appearance online. Fans of the famous work of art known as Star Wars might recognize that the names are of actual characters (note: I’m not that big of a Star Wars geek, I had to wiki those names).

The first image is one of my favorites because it was a happy accident that I created a face using the male body. The images are based on how men and women are typically drawn in super hero comics. The muscles of men are drawn with sharp angles and the women are drawn with soft curves. The backgrounds represent how I see the two sexes, one in constant contrast, the other in flowing rhythms. There are three female images to represent the muses…I guess. 😀

I like the butterfly, because they seem to appear in almost every ad for anti-depressants.

The last five images are all images of my own choosing. We were supposed to create a vector based image in illustrator (I just never had time to get my illustrator skills up to snuff) and one aimed toward children (all I could think of was creating an image of something throwing images at children).

We were working on blending modes and I, for some reason, never turned this assignment in. I missed the deadline and thought, I’ll keep it for later I guess. I like how the overlay and darken effect worked on the blade, giving the blood a jelly like look, but it didn’t work so well on the glove. I tried using puppet warp and should have used the healing brush.

This is the first of three images from the storyboard I was working on most of the semester as a personal project (one of the first productions for frogfish this spring). It will most likely not make its way into the final storyboard, primarily because I will rework the images using more shapes and less paint brush.

This was the first image I painted based on the figure I used. I have found that these wrestling figures are far more articulate than manikins. I’ve been looking for the fully articulate spiderman figure, but I have only found it online. That’s a cheap Christmas gift if any of you are…you know…thinking of that sort of thing.

This is the first image I painted using an image I found online. I like the way it came out, I’m just not a big fan of the brush strokes. I need to develop smoother, thicker strokes.

This is one of the first characters I created using all shapes and layers so that I could animate her in Flash over the holiday break. Her name is Olaf, based on my beautiful baby, and she is part of frogfish.

And here is the official first look at the frogfish cartoon logo –

I hope you enjoyed this little gallery. I can’t understand why wordrpess threw some of the text off, but…there you go. Have a merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Leave your thoughts and comments below and I will see the two of you at the new website in January.

Number 13

Sorry for the delay, ladies and gentlemen, the semester is coming toward an end and that means finals. Part of my finals is the work on the official “frogfish” website that this blog will migrate to under the “Asterias Media” tab. The Asterias Media side of frogfish is primarily ran by my wife, Laura (aka Olaf the Terrible), and you can read some of her original work at http://olaframbles2.wordpress.com/. Asterias Media will continue to publish classic horror stories like the one below, but we will soon be adding original horror fiction by emerging talent!

Speaking of the story below, this is another classic by M.R. James. If you’re a fan of Stephen King’s “1408” then it will be easy to see how this was one of those “unlucky room” stories that influenced the modern master. It was also adapted by the BBC in 2006. The story is about a man named Mr. Anderson who is staying at a hotel while doing research and discovers the hotel has rooms 12 and 14, but no 13. Until one night…

NUMBER 13 (1904)

by M.R. James

(1862 – 1936)

Originally from Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904)

This copy from The collected ghost stories of M.R. James (1931)

Edward Arnold & Co.: LONDON

This text was copied from Gaslight, an Internet discussion list which reviews one story a week from the genres of mystery, adventure and The Weird, written between 1800 and 1919

| AMONG the towns of Jutland, Viborg justly holds a high place. It is the seat of a bishopric; it has a handsome but almost entirely new cathedral, a charming garden, a lake of great beauty, and many storks. Near it is Hald, accounted one of the prettiest things in Denmark; and hard by is Finderup, where Marsk Stig murdered King Erik Glipping on St. Cecilia’s Day, in the year 1286. Fifty-six blows of square-headed iron maces were traced on Erik’s skull when his tomb was opened in the seventeenth century. But I am not writing a guide-book.There are good hotels in Viborg — Preisler’s and the Phœnix are all that can be desired. But my cousin, whose experiences I have to tell you now, went to the Golden Lion the first time that he visited Viborg. He has not been there since, and the following pages will perhaps explain the reason of his abstention.The Golden Lion is one of the very few houses in the town that were not destroyed in the great fire of 1716, which practically demolished the cathedral, the Sognekirke, the Raadhuus, and so much else that was old and interesting. It is a great red-brick house — that is, the front is of brick, with corbie steps on the gables and a tent over the door; but the courtyard into which the omnibus drives is of black and white “cage-work” in wood and plaster.The sun was declining in the heavens when my cousin walked up to the door, and the light smote full upon the imposing façade of the house. He was delighted with the old-fashioned aspect of the place, and promised himself a thoroughly satisfactory and amusing stay in an inn so typical of old Jutland.It was not business in the ordinary sense of the word that had brought Mr. Anderson to Viborg. He was engaged upon some researches into the Church history of Denmark, and it had come to his. knowledge that in the Rigsarkiv of Viborg there were papers, saved from the fire, relating to the last days of Roman Catholicism in the country. He proposed, therefore, to spend a considerable time — perhaps as much as a fortnight or three weeks — in examining and copying these, and he hoped that the Golden Lion would be able to give him a room of sufficient size to serve alike as a bedroom and a study. His wishes were explained to the landlord, and, after a certain amount of thought, the latter suggested that perhaps it might be the best way for the gentleman to look at one or two of the larger rooms and pick one for himself. It seemed a good idea.The top floor was soon rejected as entailing too much getting upstairs after the day’s work; the second floor contained no room of exactly the dimensions required; but on the first floor there was a choice of two or three rooms which would, so far as size went, suit admirably.The landlord was strongly in favour of Number 17, but Mr. Anderson pointed out that its windows commanded only the blank wall of the next house, and that it would be very dark in the afternoon. Either Number 12 or Number 14 would be better, for both of them looked on the street, and the bright evening light and the pretty view would more than compensate him for the additional amount of noise.Eventually Number 12 was selected. Like its neighbours, it had three windows, all on one side of the room; it was fairly high and unusually long. There was, of course, no fireplace, but the stove was handsome and rather old — a cast-iron erection, on the side of which was a representation of Abraham sacrificing Isaac, and the inscription, “1 Bog Mose, Cap. 22,” above. Nothing else in the room was remarkable; the only interesting picture was an old coloured print of the town, date about 1820.

Supper-time was approaching, but when Anderson, refreshed by the ordinary ablutions, descended the staircase, there were still a few minutes before the bell rang. He devoted them to examining the list of his fellow-lodgers. As is usual in Denmark, their names were displayed on a large blackboard, divided into columns and lines, the numbers of the rooms being painted in at the beginning of each line. The list was not exciting. There was an advocate, or Sagförer, a German, and some bagmen from Copenhagen. The one and only point which suggested any food for thought was the absence of any Number 13 from the tale of the rooms, and even this was a thing which Anderson had already noticed half a dozen times in his experience of Danish hotels. He could not help wondering whether the objection to that particular number, common as it is, was so widespread and so strong as to make at difficult to let a room so ticketed, and he resolved to ask the landlord if he and his colleagues in the profession had actually met with many clients who refused to be accommodated in the thirteenth room. He had nothing to tell me (I am giving the story as I heard it from him) about what passed at supper; and the evening, which was spent in unpacking and arranging his clothes, books, and papers, was not more eventful. Towards eleven o’clock he resolved to go to bed, but with him, as with a good many other people nowadays, an almost necessary preliminary to bed, if he meant to sleep, was the, reading of a few pages of print; and he now remembered, that the particular book which he had been reading in the train, and which alone would satisfy him at that present moment, was in the pocket of his greatcoat, then hanging on a peg outside the dining-room. To run down and secure it was the work of a moment, and, as the passages were by no means dark, it was not difficult for him to find his way back to his own door. So, at least, he thought; but when he arrived there, and turned the handle; the door entirely refused to open, and he caught the sound of a hasty movement towards it from within. He had tried the wrong door, of course. Was his own room to the right or to the left? He glanced at the number: it was 13. His room would be on the left; and so it was. And not before he had been in bed for some minutes, had read his wonted three or four pages of his book, blown out his light, and turned over to go to sleep, did it occur to him that, whereas on the blackboard of the hotel there had been no Number 13, there was undoubtedly a room numbered 13 in the hotel. He felt rather sorry he had not chosen it for his own. Perhaps he might have done the landlord a little service by occupying it, and given him the chance of saying that a well-born English gentleman had lived in it for three weeks and liked it very much. But probably it was used as a servant’s room or something of the kind. After all, it was most likely not so large or good a room as his own. And he looked drowsily about the room, which was fairly perceptible in the half-light from the street-lamp. It was a curious effect, he thought. Rooms usually look larger in a dim light than a full one, but this seemed to have contracted in length and grown proportionately higher. Well, well! sleep was more important than these vague ruminations — and to sleep he went. On the day after his arrival Anderson attacked the Rigsarkiv of Viborg. He was, as one might expect in Denmark, kindly received, and access to all that he wished to see was made as easy for him as possible. The documents laid before him were far more numerous and interesting than he had at all anticipated. Besides official papers, there was a large bundle of correspondence relating to Bishop Jörgen Friis, the last Roman Catholic who held the see, and in these there cropped up many amusing and what are called “intimate” details of private life and individual character. There was much talk of a house owned by the Bishop, but not inhabited by him, in the town. Its tenant was apparently somewhat of a scandal and a stumbling-block to the reforming party. He was a disgrace, they wrote, to the city; he practised secret and wicked arts, and had sold his soul to the enemy. It was of a piece with the gross corruption and superstition of the Babylonish Church that such a viper and bloodsucking Troldmand should be patronized and harboured by the Bishop. The Bishop met these reproaches boldly; he protested his own abhorrence of all such things as secret arts, and required, his antagonists to bring the matter before the proper court — of course, the spiritual court — and sift it to the bottom. No one could be more ready and willing, than himself to condemn Mag. Nicolas Francken if the evidence showed him to have been guilty of any of the crimes informally alleged against him. Anderson had not time to do more than glance at the next letter of the Protestant leader, Rasmus Nielsen, before the record office was closed for the day, but he gathered its general tenor, which was to the effect that Christian men were now no longer bound by the decisions of Bishops of Rome, and that the Bishop’s Court was not, and could not be, a fit or competent tribunal to judge so grave and weighty a cause. On leaving the office, Mr. Anderson was accompanied by the old gentleman who presided over it, and, as they walked, the conversation very naturally turned to the papers of which I have just been speaking. Herr Scavenius, the Archivist of Viborg, though very well informed as to the general run of the documents under his charge, was not a specialist in those of the Reformation period. He was much interested in what Anderson had to tell him about them. He looked forward with great pleasure, he said, to seeing the publication in which Mr. Anderson spoke of embodying their contents. “This house of the Bishop Friis,” he added, “it is a great puzzle to me where it can have stood. I have studied carefully the topography of old Viborg, but it is most unlucky — of the old- terrier of the Bishop’s property, which was made in 1560, and of which we have the greater part in the Arkiv, just the piece which had the list of the town property is missing. Never mind. Perhaps I shall some day, succeed to find him.” After taking some exercise — I forget exactly how or where — Anderson went back to the Golden Lion, his supper, his game of patience, and his bed. On the way to his room it occurred to him that he had forgotten to talk to the landlord about the omission of Number 13 from the hotel, and also that he might as well make sure that Number 13 did actually exist before he made any reference to the matter. The decision was not difficult to arrive at. There was the door with its number as plain as could be, and work of some kind was evidently going on inside it, for as he neared the door he could hear footsteps and voices, or a voice, within. During the few seconds in which he halted to make sure of the number, the footsteps ceased, seemingly very near the door, and he was a little startled at hearing a quick hissing breathing as of a person in strong excitement. He west on to his own room, and again he was surprised to find how much smaller it seemed now than it had when he selected it. It was a slight disappointment, but only slight. If he found it really not large enough, he could very easily shift to another. In the meantime he wanted something — as far as I remember it was a pocket-handkerchief — out of his portmanteau, which had been placed by the porter on a very inadequate trestle or stool against the wall at the farthest end of the room from his bed. Here was a very curious thing: the portmanteau was not to be seen. It had been moved by officious servants; doubtless the contents had been put in the wardrobe. No, none of them were there. This was vexatious. The idea of a theft he dismissed at once. Such things rarely happen in Denmark, but some piece of stupidity had certainly been performed (which is not so un- common), and the stuepige must be severely spoken to. Whatever it was that he wanted, it was not so necessary to his comfort that he could not wait till the morning for it, and he therefore settled not to ring the bell and disturb the servants. He went to the window — the right-hand window it was — and looked out on the quiet street. There was a tall building opposite, with large spaces of dead wall; no passersby; a dark night; and very little to be seen of any kind. The light was behind him, and he could see his own shadow clearly cast on the wall opposite. Also the shadow of the bearded man in Number 11 on the left, who passed to and fro in shirtsleeves once or twice, and was seen first brushing his hair, and later on in a nightgown. Also the shadow of the occupant of Number 13 on the right. This might be more interesting. Number 13 was, like himself, leaning on his elbows on the window-sill looking out into the street. He seemed to be a tall thin man — or was it by any chance a woman? — at least, it was someone who covered his or her head with some kind of drapery before going to bed, and, he thought, must be possessed of a red lamp-shade — and the lamp must be flickering very much. There was a distinct playing up and down of a dull red light on the opposite wall. He craned out a little to see if he could make any more of the figure, but beyond a fold of some light, perhaps white, material on the window-sill he could see nothing. Now came a distant step in the street, and its approach seemed to recall Number 13 to a sense of his exposed position, for very swiftly and suddenly he swept aside from the window, and his red light went out. Anderson, who had been smoking a cigarette, laid the end of it on the window-sill and went to bed. Next morning he was woke by the stuepige with hot water, etc. He roused himself, and after thinking out the correct Danish words, said as distinctly, as he could: “You mast not move my portmanteau. Where is it?” As is not uncommon, the maid laughed, and went away without making any distinct answer. Anderson, rather irritated, sat up in bed, intending to call her back, but he remained sitting up, staring straight in front of him. There was his portmanteau on its trestle, exactly where he had seen the porter put it when he first arrived. This was a rude shock for a man who prided himself on his accuracy of observation. How it could possibly have escaped him the night before he did not pretend to understand; at any rate, there it was now. The daylight showed more than the portmanteau; it let the true proportions of the room with its three windows appear, and satisfied its tenant that his choice after all had not been a bad one. When he was almost dressed he walked to the middle one of the three windows to look out at the weather. Another shock awaited him. Strangely unobservant he must have been last night. He could have sworn ten times over that he had been smoking at the right-hand window the last thing before he went to bed, and here was his cigarette-end on the sill of the middle window. He started to go down to breakfast. Rather late; but. Number 13 was later: here were his boots still outside his door — a gentleman’s boots. So then Number 13 was a man, not a woman. Just then he caught, sight of the number on the door. It was 14. He thought he must have passed Number 15 without noticing it. Three stupid mistakes in twelve hours were too much for a methodical, accurate-minded man, so he turned back to make sure. The next number to 14 was number 12, his own room. There was no Number 13 at all. After some minutes, devoted to a careful consideration of everything he had had to eat and drink during the last twenty-four hours, Anderson decided to give the question up. If his sight or his brain were giving way he would have plenty of opportunities for ascertaining that fact; if not, then he was evidently being treated to a very interesting experience. In either case the development of events would certainly be worth watching. During the day he continued his examination of the episcopal correspondence which I have already summarized. To his disappointment, it was incomplete. Only one other letter could be found which referred to the affair of Mag. Nicolas Francken. It was from the Bishop Jörgen Friis to Rasmus Nielsen. He said: “Although we are not in the least degree inclined to assent to your judgment concerning our court, and shall be prepared if need be to withstand you to the uttermost in that behalf, yet forasmuch as our trusty, and well-beloved Mag. Nicolas Francken, against whom you have dared to allege certain false and malicious charges, hath been suddenly removed from among us, it is apparent that the question for this time falls. But forasmuch as you further allege that the Apostle and Evangelist St. John in his heavenly Apocalypse describes the Holy Roman Church under the guise and symbol of the Scarlet Woman, be it known to you,” etc. Search as he might, Anderson could find no sequel to this letter nor any clue to the cause or manner of the “removal” of the casus belli. He could only suppose that Francken had died suddenly; and as there were only two days between the date of Nielsen’s last letter — when Francken was evidently still in being — and that of the Bishop’s letter, the death must have been completely unexpected. In the afternoon he paid a short visit to Hald, and took his tea at Baekkelund; nor could he notice, though he was in a somewhat nervous frame of mind, that there was any indication of such a failure of eye or brain as his experiences of the morning had led him to fear. At supper he found himself next to the landlord. “What,” he asked him, after some indifferent conversation, “is the reason why in most of the hotels one visits in this country the number thirteen is left out of the list of roams? I see you have none here.” The landlord seemed amused. “To think that you should have noticed a thing like that! I’ve thought about it once or twice myself, to tell the truth. An educated man, I’ve said, has no business with these superstitious notions. I was brought up myself here in the High School of Viborg, and our old master was always a man to set his face against anything of that kind. He’s been dead now this many years — a fine upstanding man he was, and ready with his hands as well as his head. I recollect us boys, one snowy day ——” Here he plunged into reminiscence. “Then you don’t think there is any particular objection to having a Number 13?” said Anderson. “Ah! to be sure. Well, you understand, I was brought up to the business by my poor old father. He kept an hotel in Aarhuus first, and then, when we were born, he moved to Viborg here, which was his native place, and had the Phœnix here until he died. That was in 1876. Then I started business in Silkeborg, and only the year before last I moved into this house.” Then followed more details as to the state of the house and business when first taken over. “And when you came here, was there a Number 13?” “No, no. I was going to tell you about that. You see, in a place like this, the commercial class — the travellers — are what we have to provide for in general. And put them in Number 13? Why, they’d as soon sleep in the street, or sooner. As far as I’m concerned myself, it wouldn’t make a penny difference to me what the number of my room was, and so I’ve often said to them; but they stick, to it that it brings them bad luck. Quantities of stories they have among them of men that have slept in a Number 13, and never been the same again, or lost their best customers, or — one thing and another,” said the landlord, after searching for a more graphic phrase. “Then, what do you use your Number 13 for?” said Anderson, conscious as he said the words of a curious anxiety quite disproportionate to the importance of the question. “My Number 13? Why, don’t I tell you that there isn’t such a thing in the house? I thought you might have noticed that. If there was it would be next door to your own room.” “Well, yes; only I happened to think — that is, I fancied last night that I had seen a door numbered thirteen in that passage; and, really, I am almost certain I must have been right, for I saw it the night before as well.” Of course, Herr Kristensen laughed this notion to scorn, as Anderson had expected, and emphasized with much iteration the fact that no Number 13 existed or had existed before him in that hotel. Anderson was in some ways relieved by his certainty but still puzzled, and he began to think that the best way to make sure whether he had indeed been subject to an illusion or not was to invite the landlord to his room to smoke a cigar later on in the evening. Some photographs of English towns which he had with him formed a sufficiently good excuse. Herr Kristensen was flattered by the invitation, and most willingly accepted it. At about ten o’clock he was to make his appearance, but before that Anderson had some letters to write, and retired for the purpose of writing them. He almost blushed to himself, at confessing it, but he could not deny that it was the fact that he was becoming quite nervous about the question of the existence of Number 13; so much so that he approached his room by way of Number 11, in order that he might not be obliged to pass the door, or the place where the door ought to be. He looked quickly and suspiciously about the room when he entered it, but there was nothing, beyond that indefinable air of being smaller than usual, to warrant any misgivings. There was no question of the presence or absence of his portmanteau to-night. He had himself emptied it of its contents and lodged it under his bed. With a certain effort, he dismissed the thought of Number 13 from his mind, and sat down to his writing. His neighbours were quiet enough. Occasionally a door opened in the passage and a pair of boots was thrown out, or a bagman walked past humming to himself, and outside, from time to time a cart thundered over the atrocious cobble-stones, or a quick step hurried along the flags. Anderson finished his letters, ordered whisky and soda, and then went to the window studied the dead wall opposite and the shadows upon it. As far as he could remember, Number 14 had been occupied by the lawyer, a staid man, who said little at meals, being generally engaged in studying a small bundle of papers beside his plate. Apparently, however, he was in the habit of giving vent to his animal spirits when alone. Why else should he be dancing? The shadow from the next room evidently showed that he was. Again and again his thin form crossed the window, his arms waved, and a gaunt leg was kicked up with surprising agility. He seemed to be barefooted, and the floor must be well laid, for no sound betrayed his movements: Sagförer Herr Anders Jensen, dancing at ten o’clock at night in a hotel bedroom, seemed a fitting subject for a historical painting in the grand style; and Anderson’s thoughts, like those of Emily in the Mysteries of Udolpho, began to “arrange themselves in the following lines”:

Had not the landlord at this moment knocked at the door, it is probable that quite a long poem might have been laid before the reader. To judge from his look of surprise when he found himself in the room, Herr Kristensen was struck, as Anderson had been, by something unusual in its aspect. But he made no remark. Anderson’s photographs interested him mightily, and formed the text of many autobiographical discourses. Nor is it quite clear how the conversation could have been diverted into the desired channel of Number 13, had not the lawyer at this moment begun to sing, and to sing in a manner which could leave no doubt in anyone’s mind that he was either exceedingly drunk or raving mad. It was a high, thin voice that they heard, and it seemed dry, as if from long disuse. Of words or tune there was no question. It went sailing up to a surprising height, and was carried down with a despairing moan as of a winter wind in a hollow chimney, or an organ whose wind fails suddenly. It was a really horrible sound, and Anderson felt that if he had been alone he must have fled for refuge and society to some neighbour bagman’s room. The landlord sat open-mouthed. “I don’t understand it,” he said at last; wiping his forehead. “It is dreadful. I have heard it once before, but I made sure it was a cat.” “Is he mad?” said Anderson. “He must be; and what a sad thing! Such a good customer, too, and so successful in his business; by what I hear, and a young family, to bring up.” Just then came an impatient knock at the door, and the knocker entered, without waiting to be asked. It was the lawyer, in deshabille and very rough-haired; and very angry he looked. “I beg pardon, sir,” he said, “but I should be much obliged if you would kindly desist. desist ——” Here he stopped, for it was evident that neither of the persons before him was responsible for the disturbance; and after a moment’s lull it swelled forth again more wildly than before. “But what in the name of Heaven does it mean?” broke out the lawyer. “Where is it? Who is it? Am I going out of my mind?” “Surely, Herr, Jensen, it comes from your room next door? Isn’t there a cat or something stuck in the chimney?” This was the best that occurred to Anderson to say, and he realized its futility as he spoke; but anything was better than to stand and listen to that horrible voice, and look at the broad, white face of the landlord, all perspiring and quivering as he clutched the arms of his chair. “Impossible,” said the lawyer, “impossible. There is no chimney. I came here because I was convinced the noise was going on here. It was certainly in the next room to mine.” “Was there no door between yours and mine?” said Anderson eagerly. “No,” sir,” said Herr Jensen, rather sharply. “At least, not this morning.” “Ah!” said Anderson. “Nor to-night?” “I am not sure,” said the lawyer, with some hesitation. Suddenly the crying or singing voice in the nest room died away, and the singer was heard seemingly to laugh to himself in a crooning manner. The three men actually shivered at the sound. Then there was a silence. “Come,” said the lawyer, “what have you to say; Herr Kristensen? What does this mean?” “Good Heaven!” said Kristensen. “How should I tell! I know no more than you, gentlemen. I pray I may never hear such a noise again.” “So do I,” said Herr Jensen, and he added something under his breath. Anderson thought it sounded like the last words of the Psalter, “omnis spiritus laudet Dominum,” but he could not be sure. “But we must do something,” said Anderson — “the three of us. Shall we go and investigate in the next room?” “But that is Herr Jensen’s room,” wailed the landlord. “It is no use; he has come from there himself.” “I am not so sure,” said Jensen. “I think this gentleman is right: we must go and see.” The only weapons of defence that could be mustered on the spot were a stick and umbrella. The expedition went out into the passage, not without quakings. There was a deadly quiet outside, but a light shone from under the next door. Anderson and Jensen approached it. The latter turned the handle, and gave a sudden vigorous push. No use. The door stood fast. “Herr Kristensen,” said Jensen, “will you go and fetch the strongest servant you have in the place? We must see this through.” The landlord nodded, and hurried off, glad to be away from the scene of action. Jensen and Anderson remained outside looking at the door. “It is Number 13, you see,” said the latter. “Yes; there is your door; and there is mine,” said Jensen. “My room has three windows in the daytime,” said Anderson, with difficulty suppressing a nervous laugh. “By George, so has mine!” said the lawyer, turning and looking at Anderson. His back was now to the door. In that moment the door opened, and an arm came out and clawed at his shoulder. It was clad in ragged, yellowish linen, and the bare skin, where it could be seen, had long grey hair upon it. Anderson was just in time to pull Jensen out of its reach with a cry of disgust and fright, when the door shut again, and a low laugh was heard. Jensen had seen nothing, but when Anderson hurriedly told him what a risk he had run, he fell into a great state of agitation, and suggested that they should retire from the enterprise and lock themselves up in one or other of their rooms. However, while he was developing this plan, the landlord and two able-bodied men arrived on the scene, all looking rather serious and alarmed. Jensen met them with a torrent of description and explanation, which did not at all tend to encourage them for the fray. The men dropped the crowbars they had brought, and said flatly that they were not going to risk their throats in that devil’s den. The landlord was miserably nervous and undecided, conscious that if the danger were not faced his hotel was ruined, and very loth to face it himself. Luckily Anderson hit upon a way of rallying the demoralized force. “Is this,” he said, “the Danish courage I have heard so much of? It isn’t a German in there; and if it was, we are five to one.” The two servants and Jensen were stung into action by this, and made a dash at the door. “Stop!” laid Anderson. “Don’t lose your heads. You stay out here with the light, landlord, and one of you two men break in the door, and don’t go in when it gives way.” The men nodded, and the younger stepped forward, raised his crowbar, and dealt a tremendous blow on the upper panel. The result was not in the least what any of them anticipated. There was no cracking or rending of wood — only a dull sound, as if the solid wall had been struck. The man dropped his tool with a shout, and began rubbing his elbow. His cry drew their eyes upon him for a moment; then Anderson looked at the door again. It was gone; the plaster wall of the passage stared him in the face, with a considerable gash in it where the crowbar had struck it. Number 13 had passed out of existence. For a brief space they stood perfectly still, gazing at the blank wall. An early cock in the yard beneath was heard to crow; and as Anderson glanced in the direction of the sound, he saw through the window at tie end of the long passage that the eastern sky was paling to the dawn. * * * * * * “Perhaps,” said the landlord, with hesitation, “you gentlemen would like another room for to-night — a double-bedded one?” Neither Jensen nor Anderson was averse to the suggestion. They felt inclined to hunt in couples after their late experience. It was found convenient, when each of them went to his room to collect the articles he wanted for the night, that the other should go with him and hold the candle. They noticed that both Number 12 and Number 14 had three windows. Next morning the same party reassembled in Number 12. The landlord was naturally anxious to avoid engaging outside help, and yet it was imperative that the mystery attaching to that part of the house should be cleared up. Accordingly the two servants had been induced to take upon them the function of carpenters. The furniture was cleared away, and, at the cost of a good many irretrievably damaged planks, that portion of the floor was taken up which lay nearest to Number 14. You will naturally suppose that a skeleton — say that of Mag. Nicolas Francken — was discovered. That was not so. What they did find lying between the beams which supported the flooring was a small copper box. In it was a neatly-folded vellum document, with about twenty lines of writing. Both Anderson and Jensen (who proved to be something of a palæographer) were much excited by this discovery, which promised to afford the key to these extraordinary phenomena. * * * * * * I possess a copy of an astrological work which I have never read. It has by way of frontispiece, a woodcut by Hans Sebald Beham, representing a number of sages seated round a table. This detail may enable connoisseurs to identify the book. I cannot myself recollect its title, and it is not at this moment within reach; but the fly-leaves of it are covered with writing, and, during the ten years in which I have owned the volume, I have not been able to determine which way up this writing ought to be read, much less in what language it is. Not dissimilar was the position of Anderson and Jensen after the protracted examination to which they submitted the document in the copper box. After two days’ contemplation of it, Jensen, who was the bolder, spirit of the two, hazarded the conjecture that the language was either Latin or Old Danish. Anderson ventured upon no surmises, and was very willing to surrender the box and the parchment to the Historical Society of Viborg to be placed in their museum. I had the whole story from him a few months later, as we sat in a wood near Upsala, after a visit to the library there, where we — or, rather, I — had laughed over the contract by which Daniel Salthenius (in later life Professor of Hebrew at Königsberg) sold himself to Satan. Anderson was not really amused. “Young idiot!” he said, meaning Salthenius, who was only an undergraduate when he committed that indiscretion, “how did he know what company he was courting?” And when I suggested the usual considerations he only grunted. That same afternoon he told me what you have read; but he refused to draw any inferences from it, and to assent to any that I drew for him. |

Be sure to leave a comment and let us know what you think of this story or if there are other classic stories you’d like us to feature.

Related articles

- Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by M. R. James (apaperbacklife.wordpress.com)

- Casting the Runes and Other Ghost Stories (shelflove.wordpress.com)

- Ghost Stories Volume 5 DVD Review (thepeoplesmovies.com)

A Watcher by the Dead

A Watcher By the Dead by Ambrose Bierce

I am currently producing an animatic for “The Death of Halpin Frayser” using Photoshop and Flash Pro. “The Death of Halpin Frayser” will be the first of three Ambrose Bierce short narratives that I will write/direct/produce at the start of next year. The second is “A Watcher By the Dead.” In the story a macabre bet has deadly consequences when a gambler accepts the challenge of spending the night in a locked room with a dead body. Bierce does an excellent job setting the atmosphere and putting the audience in the room, feeling the weight of the darkness and constant awareness of the corpse in the room. In my own adaptation of this story I put a bit more focus on the characters that inhabit the tale (as I am want to do) and another twist on the already twisted ending. I’ve attached a copy of my adaptation below. Please read both versions and tell me what you think of the two stories.

Enjoy.

First published in the San Francisco Examiner, December 29, 1889.

Included in Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1891).

I

In an upper room of an unoccupied dwelling in the part of San Francisco known as North Beach lay the body of a man, under a sheet. The hour was near nine in the evening; the room was dimly lighted by a single candle. Although the weather was warm, the two windows, contrary to the custom which gives the dead plenty of air, were closed and the blinds drawn down. The furniture of the room consisted of but three pieces—an arm-chair, a small reading-stand supporting the candle, and a long kitchen table, supporting the body of the man. All these, as also the corpse, seemed to have been recently brought in, for an observer, had there been one, would have seen that all were free from dust, whereas everything else in the room was pretty thickly coated with it, and there were cobwebs in the angles of the walls.

Under the sheet the outlines of the body could be traced, even the features, these having that unnaturally sharp definition which seems to belong to faces of the dead, but is really characteristic of those only that have been wasted by disease. From the silence of the room one would rightly have inferred that it was not in the front of the house, facing a street. It really faced nothing but a high breast of rock, the rear of the building being set into a hill.

As a neighboring church clock was striking nine with an indolence which seemed to imply such an indifference to the flight of time that one could hardly help wondering why it took the trouble to strike at all, the single door of the room was opened and a man entered, advancing toward the body. As he did so the door closed, apparently of its own volition; there was a grating, as of a key turned with difficulty, and the snap of the lock bolt as it shot into its socket. A sound of retiring footsteps in the passage outside ensued, and the man was to all appearance a prisoner. Advancing to the table, he stood a moment looking down at the body; then with a slight shrug of the shoulders walked over to one of the windows and hoisted the blind. The darkness outside was absolute, the panes were covered with dust, but by wiping this away he could see that the window was fortified with strong iron bars crossing it within a few inches of the glass and imbedded in the masonry on each side. He examined the other window. It was the same. He manifested no great curiosity in the matter, did not even so much as raise the sash. If he was a prisoner he was apparently a tractable one. Having completed his examination of the room, he seated himself in the arm-chair, took a book from his pocket, drew the stand with its candle alongside and began to read.

The man was young—not more than thirty—dark in complexion, smooth-shaven, with brown hair. His face was thin and high-nosed, with a broad forehead and a “firmness” of the chin and jaw which is said by those having it to denote resolution. The eyes were gray and steadfast, not moving except with definitive purpose. They were now for the greater part of the time fixed upon his book, but he occasionally withdrew them and turned them to the body on the table, not, apparently, from any dismal fascination which under such circumstances it might be supposed to exercise upon even a courageous person, nor with a conscious rebellion against the contrary influence which might dominate a timid one. He looked at it as if in his reading he had come upon something recalling him to a sense of his surroundings. Clearly this watcher by the dead was discharging his trust with intelligence and composure, as became him.

After reading for perhaps a half-hour he seemed to come to the end of a chapter and quietly laid away the book. He then rose and taking the reading-stand from the floor carried it into a corner of the room near one of the windows, lifted the candle from it and returned to the empty fireplace before which he had been sitting.

A moment later he walked over to the body on the table, lifted the sheet and turned it back from the head, exposing a mass of dark hair and a thin face-cloth, beneath which the features showed with even sharper definition than before. Shading his eyes by interposing his free hand between them and the candle, he stood looking at his motionless companion with a serious and tranquil regard. Satisfied with his inspection, he pulled the sheet over the face again and returning to the chair, took some matches off the candlestick, put them in the side pocket of his sack-coat and sat down. He then lifted the candle from its socket and looked at it critically, as if calculating how long it would last. It was barely two inches long; in another hour he would be in darkness. He replaced it in the candlestick and blew it out.

II

In a physician’s office in Kearny Street three men sat about a table, drinking punch and smoking. It was late in the evening, almost midnight, indeed, and there had been no lack of punch. The gravest of the three, Dr. Helberson, was the host—it was in his rooms they sat. He was about thirty years of age; the others were even younger; all were physicians.

“The superstitious awe with which the living regard the dead,” said Dr. Helberson, “is hereditary and incurable. One needs no more be ashamed of it than of the fact that he inherits, for example, an incapacity for mathematics, or a tendency to lie.”

The others laughed. “Oughtn’t a man to be ashamed to lie?” asked the youngest of the three, who was in fact a medical student not yet graduated.

“My dear Harper, I said nothing about that. The tendency to lie is one thing; lying is another.”

“But do you think,” said the third man, “that this superstitious feeling, this fear of the dead, reasonless as we know it to be, is universal? I am myself not conscious of it.”

“Oh, but it is ‘in your system’ for all that,” replied Helberson; “it needs only the right conditions—what Shakespeare calls the ‘confederate season’—to manifest itself in some very disagreeable way that will open your eyes. Physicians and soldiers are of course more nearly free from it than others.”

“Physicians and soldiers!—why don’t you add hangmen and headsmen? Let us have in all the assassin classes.”

“No, my dear Mancher; the juries will not let the public executioners acquire sufficient familiarity with death to be altogether unmoved by it.”

Young Harper, who had been helping himself to a fresh cigar at the sideboard, resumed his seat. “What would you consider conditions under which any man of woman born would become insupportably conscious of his share of our common weakness in this regard?” he asked, rather verbosely.

“Well, I should say that if a man were locked up all night with a corpse—alone—in a dark room—of a vacant house—with no bed covers to pull over his head—and lived through it without going altogether mad, he might justly boast himself not of woman born, nor yet, like Macduff, a product of Cæsarean section.”

“I thought you never would finish piling up conditions,” said Harper, “but I know a man who is neither a physician nor a soldier who will accept them all, for any stake you like to name.”

“Who is he?”

“His name is Jarette—a stranger here; comes from my town in New York. I have no money to back him, but he will back himself with loads of it.”

“How do you know that?”

“He would rather bet than eat. As for fear—I dare say he thinks it some cutaneous disorder, or possibly a particular kind of religious heresy.”

“What does he look like?” Helberson was evidently becoming interested.

“Like Mancher, here—might be his twin brother.”

“I accept the challenge,” said Helberson, promptly.

“Awfully obliged to you for the compliment, I’m sure,” drawled Mancher, who was growing sleepy. “Can’t I get into this?”

“Not against me,” Helberson said. “I don’t want your money.”

“All right,” said Mancher; “I’ll be the corpse.”

The others laughed.

The outcome of this crazy conversation we have seen.

III

In extinguishing his meagre allowance of candle Mr. Jarette’s object was to preserve it against some unforeseen need. He may have thought, too, or half thought, that the darkness would be no worse at one time than another, and if the situation became insupportable it would be better to have a means of relief, or even release. At any rate it was wise to have a little reserve of light, even if only to enable him to look at his watch.

No sooner had he blown out the candle and set it on the floor at his side than he settled himself comfortably in the arm-chair, leaned back and closed his eyes, hoping and expecting to sleep. In this he was disappointed; he had never in his life felt less sleepy, and in a few minutes he gave up the attempt. But what could he do? He could not go groping about in absolute darkness at the risk of bruising himself—at the risk, too, of blundering against the table and rudely disturbing the dead. We all recognize their right to lie at rest, with immunity from all that is harsh and violent. Jarette almost succeeded in making himself believe that considerations of this kind restrained him from risking the collision and fixed him to the chair.

While thinking of this matter he fancied that he heard a faint sound in the direction of the table—what kind of sound he could hardly have explained. He did not turn his head. Why should he—in the darkness? But he listened—why should he not? And listening he grew giddy and grasped the arms of the chair for support. There was a strange ringing in his ears; his head seemed bursting; his chest was oppressed by the constriction of his clothing. He wondered why it was so, and whether these were symptoms of fear. Then, with a long and strong expiration, his chest appeared to collapse, and with the great gasp with which he refilled his exhausted lungs the vertigo left him and he knew that so intently had he listened that he had held his breath almost to suffocation. The revelation was vexatious; he arose, pushed away the chair with his foot and strode to the centre of the room. But one does not stride far in darkness; he began to grope, and finding the wall followed it to an angle, turned, followed it past the two windows and there in another corner came into violent contact with the reading-stand, overturning it. It made a clatter that startled him. He was annoyed. “How the devil could I have forgotten where it was?” he muttered, and groped his way along the third wall to the fireplace. “I must put things to rights,” said he, feeling the floor for the candle.

Having recovered that, he lighted it and instantly turned his eyes to the table, where, naturally, nothing had undergone any change. The reading-stand lay unobserved upon the floor: he had forgotten to “put it to rights.” He looked all about the room, dispersing the deeper shadows by movements of the candle in his hand, and crossing over to the door tested it by turning and pulling the knob with all his strength. It did not yield and this seemed to afford him a certain satisfaction; indeed, he secured it more firmly by a bolt which he had not before observed. Returning to his chair, he looked at his watch; it was half-past nine. With a start of surprise he held the watch at his ear. It had not stopped. The candle was now visibly shorter. He again extinguished it, placing it on the floor at his side as before.

Mr. Jarette was not at his ease; he was distinctly dissatisfied with his surroundings, and with himself for being so. “What have I to fear?” he thought. “This is ridiculous and disgraceful; I will not be so great a fool.” But courage does not come of saying, “I will be courageous,” nor of recognizing its appropriateness to the occasion. The more Jarette condemned himself, the more reason he gave himself for condemnation; the greater the number of variations which he played upon the simple theme of the harmlessness of the dead, the more insupportable grew the discord of his emotions. “What!” he cried aloud in the anguish of his spirit, “what! shall I, who have not a shade of superstition in my nature—I, who have no belief in immortality—I, who know (and never more clearly than now) that the after-life is the dream of a desire—shall I lose at once my bet, my honor and my self-respect, perhaps my reason, because certain savage ancestors dwelling in caves and burrows conceived the monstrous notion that the dead walk by night?—that—” Distinctly, unmistakably, Mr. Jarette heard behind him a light, soft sound of footfalls, deliberate, regular, successively nearer!

IV

Just before daybreak the next morning Dr. Helberson and his young friend Harper were driving slowly through the streets of North Beach in the doctor’s coupé.

“Have you still the confidence of youth in the courage or stolidity of your friend?” said the elder man. “Do you believe that I have lost this wager?”

“I know you have,” replied the other, with enfeebling emphasis.

“Well, upon my soul, I hope so.”

It was spoken earnestly, almost solemnly. There was a silence for a few moments.

“Harper,” the doctor resumed, looking very serious in the shifting half-lights that entered the carriage as they passed the street lamps, “I don’t feel altogether comfortable about this business. If your friend had not irritated me by the contemptuous manner in which he treated my doubt of his endurance —a purely physical quality—and by the cool incivility of his suggestion that the corpse be that of a physician, I should not have gone on with it. If anything should happen we are ruined, as I fear we deserve to be.”

“What can happen? Even if the matter should be taking a serious turn, of which I am not at all afraid, Mancher has only to ‘resurrect’ himself and explain matters. With a genuine ‘subject’ from the dissecting-room, or one of your late patients, it might be different.”

Dr. Mancher, then, had been as good as his promise; he was the “corpse.”

Dr. Helberson was silent for a long time, as the carriage, at a snail’s pace, crept along the same street it had traveled two or three times already. Presently he spoke: “Well, let us hope that Mancher, if he has had to rise from the dead, has been discreet about it. A mistake in that might make matters worse instead of better.”

“Yes,” said Harper, “Jarette would kill him. But, Doctor”—looking at his watch as the carriage passed a gas lamp—”it is nearly four o’clock at last.”

A moment later the two had quitted the vehicle and were walking briskly toward the long-unoccupied house belonging to the doctor in which they had immured Mr. Jarette in accordance with the terms of the mad wager. As they neared it they met a man running. “Can you tell me,” he cried, suddenly checking his speed, “where I can find a doctor?”

“What’s the matter?” Helberson asked, non-committal.

“Go and see for yourself,” said the man, resuming his running.

They hastened on. Arrived at the house, they saw several persons entering in haste and excitement. In some of the dwellings near by and across the way the chamber windows were thrown up, showing a protrusion of heads. All heads were asking questions, none heeding the questions of the others. A few of the windows with closed blinds were illuminated; the inmates of those rooms were dressing to come down. Exactly opposite the door of the house that they sought a street lamp threw a yellow, insufficient light upon the scene, seeming to say that it could disclose a good deal more if it wished. Harper paused at the door and laid a hand upon his companion’s arm. “It is all up with us, Doctor,” he said in extreme agitation, which contrasted strangely with his free-and-easy words; “the game has gone against us all. Let’s not go in there; I’m for lying low.”

“I’m a physician,” said Dr. Helberson, calmly; “there may be need of one.”

They mounted the doorsteps and were about to enter. The door was open; the street lamp opposite lighted the passage into which it opened. It was full of men. Some had ascended the stairs at the farther end, and, denied admittance above, waited for better fortune. All were talking, none listening. Suddenly, on the upper landing there was a great commotion; a man had sprung out of a door and was breaking away from those endeavoring to detain him. Down through the mass of affrighted idlers he came, pushing them aside, flattening them against the wall on one side, or compelling them to cling to the rail on the other, clutching them by the throat, striking them savagely, thrusting them back down the stairs and walking over the fallen. His clothing was in disorder, he was without a hat. His eyes, wild and restless, had in them something more terrifying than his apparently superhuman strength. His face, smooth-shaven, was bloodless, his hair frost-white.

As the crowd at the foot of the stairs, having more freedom, fell away to let him pass Harper sprang forward. “Jarette! Jarette!” he cried.

Dr. Helberson seized Harper by the collar and dragged him back. The man looked into their faces without seeming to see them and sprang through the door, down the steps, into the street, and away. A stout policeman, who had had inferior success in conquering his way down the stairway, followed a moment later and started in pursuit, all the heads in the windows—those of women and children now—screaming in guidance.

The stairway being now partly cleared, most of the crowd having rushed down to the street to observe the flight and pursuit, Dr. Helberson mounted to the landing, followed by Harper. At a door in the upper passage an officer denied them admittance. “We are physicians,” said the doctor, and they passed in. The room was full of men, dimly seen, crowded about a table. The newcomers edged their way forward and looked over the shoulders of those in the front rank. Upon the table, the lower limbs covered with a sheet, lay the body of a man, brilliantly illuminated by the beam of a bull’s-eye lantern held by a policeman standing at the feet. The others, excepting those near the head—the officer himself—all were in darkness. The face of the body showed yellow, repulsive, horrible! The eyes were partly open and upturned and the jaw fallen; traces of froth defiled the lips, the chin, the cheeks. A tall man, evidently a doctor, bent over the body with his hand thrust under the shirt front. He withdrew it and placed two fingers in the open mouth. “This man has been about six hours dead,” said he. “It is a case for the coroner.”

He drew a card from his pocket, handed it to the officer and made his way toward the door.

“Clear the room—out, all!” said the officer, sharply, and the body disappeared as if it had been snatched away, as shifting the lantern he flashed its beam of light here and there against the faces of the crowd. The effect was amazing! The men, blinded, confused, almost terrified, made a tumultuous rush for the door, pushing, crowding, and tumbling over one another as they fled, like the hosts of Night before the shafts of Apollo. Upon the struggling, trampling mass the officer poured his light without pity and without cessation. Caught in the current, Helberson and Harper were swept out of the room and cascaded down the stairs into the street.

“Good God, Doctor! did I not tell you that Jarette would kill him?” said Harper, as soon as they were clear of the crowd.

“I believe you did,” replied the other, without apparent emotion.

They walked on in silence, block after block. Against the graying east the dwellings of the hill tribes showed in silhouette. The familiar milk wagon was already astir in the streets; the baker’s man would soon come upon the scene; the newspaper carrier was abroad in the land.

“It strikes me, youngster,” said Helberson, “that you and I have been having too much of the morning air lately. It is unwholesome; we need a change. What do you say to a tour in Europe?”

“When?”

“I’m not particular. I should suppose that four o’clock this afternoon would be early enough.”

“I’ll meet you at the boat,” said Harper

.

V

Seven years afterward these two men sat upon a bench in Madison Square, New York, in familiar conversation. Another man, who had been observing them for some time, himself unobserved, approached and, courteously lifting his hat from locks as white as frost, said: “I beg your pardon, gentlemen, but when you have killed a man by coming to life, it is best to change clothes with him, and at the first opportunity make a break for liberty.”

Helberson and Harper exchanged significant glances. They were obviously amused. The former then looked the stranger kindly in the eye and replied:

“That has always been my plan. I entirely agree with you as to its advant—”

He stopped suddenly, rose and went white. He stared at the man, open-mouthed; he trembled visibly.

“Ah!” said the stranger, “I see that you are indisposed, Doctor. If you cannot treat yourself Dr. Harper can do something for you, I am sure.”

“Who the devil are you?” said Harper, bluntly.

The stranger came nearer and, bending toward them, said in a whisper: “I call myself Jarette sometimes, but I don’t mind telling you, for old friendship, that I am Dr. William Mancher.”

The revelation brought Harper to his feet. “Mancher!” he cried; and Helberson added: “It is true, by God!”

“Yes,” said the stranger, smiling vaguely, “it is true enough, no doubt.”

He hesitated and seemed to be trying to recall something, then began humming a popular air. He had apparently forgotten their presence.

“Look here, Mancher,” said the elder of the two, “tell us just what occurred that night—to Jarette, you know.”

“Oh, yes, about Jarette,” said the other. “It’s odd I should have neglected to tell you—I tell it so often. You see I knew, by over-hearing him talking to himself, that he was pretty badly frightened. So I couldn’t resist the temptation to come to life and have a bit of fun out of him—I couldn’t really. That was all right, though certainly I did not think he would take it so seriously; I did not, truly. And afterward—well, it was a tough job changing places with him, and then—damn you! you didn’t let me out!”

Nothing could exceed the ferocity with which these last words were delivered. Both men stepped back in alarm.

“We?—why—why,” Helberson stammered, losing his self-possession utterly, “we had nothing to do with it.”

“Didn’t I say you were Drs. Hell-born and Sharper?” inquired the man, laughing.

“My name is Helberson, yes; and this gentleman is Mr. Harper,” replied the former, reassured by the laugh. “But we are not physicians now; we are—well, hang it, old man, we are gamblers.”

And that was the truth.

“A very good profession—very good, indeed; and, by the way, I hope Sharper here paid over Jarette’s money like an honest stakeholder. A very good and honorable profession,” he repeated, thoughtfully, moving carelessly away; “but I stick to the old one. I am High Supreme Medical Officer of the Bloomingdale Asylum; it is my duty to cure the superintendent.”

A Watcher by the Dead

story by Ambrose Bierce

adaptation by Kermet Merl Key

SUPER: “A WATCHER BY THE DEAD.”

FADE IN:

INT. CABIN – NIGHT

On a table under a sheet lies the body of a man.

The outlines of the body can be traced, even the features.

THE CABIN IS DIMLY LIT BY A SINGLE CANDLE.

The windows are closed and blinds drawn down. There are cobwebs in the angles of the walls.

The furniture consists of but three pieces – an armchair, a small reading stand supporting the candle, and the table. All are free from dust, whereas everything else in the room is pretty thickly coated with it. A neighboring church clock STRIKES nine.

The single door opens and JARETTE, enters and advances toward the body. As he does the door closes. There is the GRATING of a key turned with difficulty, and the SNAP of the lock bolt as it shot into its socket. A SOUND of retiring footsteps in the passage outside ensue.

Jarette stands a moment looking down at the body; then with a slight shrug of the shoulders walks over to one of the windows and hoists the blind.

JARETTE’S POV

He wipes the dust away and sees that the window is fortified with strong iron bars imbedded in the masonry on each side.

BACK TO SCENE

He examines the other window without raising the sash.

He sits in the arm-chair, takes a pistol from his coat and sets it on the nightstand, then takes a book from his pocket, draws the stand with its candle alongside and reads.

He occasionally eyes the body.

DISSOLVE TO:

Jarette lays the book aside, rubs his eyes and rises. He puts the pistol back in his coat, and takes the reading-stand from the floor.

He carries it into a corner of the room near one of the windows, lifts the candle from it and returns to the empty fireplace.

He walks over to the body, lifts the sheet and turns it back from the head.

JARETTE’S POV

He sees a mass of dark hair and a thin face-cloth, beneath which the features show with even sharper definition than before.

BACK TO SCENE

He shades his eyes by interposing his free hand between them and the candle. Satisfied with his inspection, he pulls the sheet over the face again and returns to the chair, takes some matches off the candlestick, puts them in his side pocket and sits down.

He lifts the candle from its socket and looks at it critically, calculating how long it would last.

He replaces it in the candlestick and blows it out.

He settles himself comfortably in the arm-chair, leans back and closes his eyes. He stirs.

He hears a faint SOUND in the direction of the table.

He strains to listen, breath held, for a long moment. He has a moment of vertigo and exhales long and strong then gasps to refill his lungs.

He rises, pushes away the chair with his foot and strides to the center of the room.

He gropes, and finds the wall, follows it to an angle, turns, follows it past the two windows and there in another corner overturns the reading-stand. The clatter startles him.

JARETTE

Shit! Where is it?

(gropes)

I’ve got to put it back.

He takes the candlestick off the fireplace, lights it, and instantly turns his eyes to the table where the body remains.

He looks all about the room…

…dispersing the deeper shadows by movements of the candle and crosses over to the door.

He tests it, turning and pulling the knob with all his strength. Seeming satisfied, he returns to his chair, and looks at his watch.

INSERT WATCH

It is half-past nine.

BACK TO SCENE

With a start of surprise he holds the watch to his ear.

He looks at the candle, now visibly shorter and pockets the watch. He again extinguishes the candle, placing it on the floor at his side as before.

JARETTE (CONT’D)

This is ridiculous. I am not a coward.

He gnaws at his thumbnail.

JARETTE (CONT’D)

What! What! I’m not superstitious. I don’t believe in heaven or hell. I’ll lose the bet, my honor and my self-respect, perhaps my reason, because people dwelling in caves once believed that the dead walk by night?

Jarette hears behind him the soft SOUND of footfalls!

He takes the pistol from his coat. Spins. Waves the gun at the darkness. He drops to his knees in search of the candle. The matches.

A dark figure shuffles toward him.

His hand lands upon a match. He strikes it against the floor.

He holds the lit match next to the barrel of the pistol and aims.

The illuminated figure looks very much like Jarette! It opens its mouth! Jarette fires.

Jarette drops the match and is in darkness as he hears the SOUND of a key grating into the lock. The door opens behind him. Blinding light…

DISSOLVE TO:

INT. TAVERN (FLASHBACK) – NIGHT

Three men sit at a table drinking and smoking. The bar is nearly empty. A waitress stacks chairs behind them.

DR. HELBERSON, the eldest, leans back.

DR. HELBERSON

The superstitious awe with which the living regard the dead is hereditary and incurable. One needs no more be ashamed of it than the fact that he inherits an incapacity for mathematics, or a tendency to lie.

The other two laugh.

HARPER, the youngest, leans forward.

HARPER

A man should be ashamed to lie?

DR. HELBERSON

The tendency to lie is one thing; lying is another.

MANCHER, (face unseen), takes a drink.

MANCHER

But do you think that this superstitious feeling, this fear of the dead, is universal?

DR. HELBERSON

It’s in your system; all that it needs is the right condition, what Shakespeare calls the ‘confederate season,’ to manifest itself in some very disagreeable way that will open your eyes. Physicians and soldiers are of course more nearly free from it than others.

MANCHER

Physicians and soldiers! Why not executioners? Throw in all the killers.

HARPER

What conditions would you consider which any man of woman born would become insupportably conscious of his share of this common weakness?

DR. HELBERSON

If a man were locked up all night with a corpse alone in a dark room, of a vacant house, with no bed covers to pull over his head, and lived through it without going altogether mad, he might justly boast himself not of woman born, nor yet, like Macduff, a product of Caesarean section.

HARPER

I thought you never would finish piling up conditions.

(laughter)

But I know a man who is neither a physician nor a soldier who will accept them all, for any stake you like to name. His name is Jarette. He’s from New York. I have no money to back him, but he will back himself with loads of it.

MANCHER

How do you know that?

HARPER

He would rather bet than eat. He thinks fear is a disease, or a religious heresy.

DR. HELBERSON

I accept the challenge.

HARPER:

He even looks like Mancher, here could be his twin.

MANCHER, leans into the light and is revealed to be the body on the table. He could be Jarette’s twin.

MANCHER

Handsome fella. Can I get into this?

DR. HELBERSON

Not against me, the bet’s with Jarette.

MANCHER

(grinning)

All right then, I’ll be the corpse.

The others laugh.

FADE OUT:

Related articles

- Read “A Baby Tramp,” A Short Story by Ambrose Bierce (biblioklept.org)

- Mailman Thought Corpse Was Halloween Decoration, Delivers Dead Man’s Mail (dreamindemon.com)

- “Indiana wants me, Lord I can’t go back there.” (frogfishmedia.wordpress.com)

“Engineer the future now…Part 2”

Today, we’re back to posting about what’s going on in the classroom and for this assignment we’re supposed to discuss what our “dream job” may be or where we see ourselves employed after we graduate from IUPUI.

First, I see my self as self-employed or freelancing. I am attending IUPUI for three reasons only, resources, networking and new skills. For example, as a student at IUPUI I was able to purchase Adobe Design and Web Premium CS6 for $20 and access to lynda.com. Those two resource alone would have cost about $750 (about $375 each, with a one year subscription to Lynda.com). There is also access to video production equipment that I have yet to use, so overall that’s at least worth the cost of one semester. Then there’s the networking. I’ve recently joined a group of young film-making students. We’re all passionate about film and excited to build our portfolios together. This Friday will be my first opportunity to actually meet with the group in person. Finally, there’s the new skills. While I’m learning a lot from the tutorials on lynda.com, film making is a collaborative medium. There are many things you can by yourself, like writing, storyboards and even animatics but if you into to create video all the tutorials in the world will not make up for actual on the set experience. Therefore, through the resources, networks and new skills at IUPUI I should have not only an impressive portfolio, but the foundation for my career in video production and storytelling.

Upon graduation I will have to complete a capstone project my last semester at IUPUI and my goal is to use the resources, networks and skills to make a feature film. I will have, by the time I graduate, made several short films (I am lining up at least 3 for the upcoming Spring semester alone) and developed a website/production company with my wife, Laura, called FrogFish.com, where Frog Experiments (my videos) and Asterias Media (her written stories) come together to display the projects I’ve developed during my time at IUPUI, promote local authors and entertain audiences. This website and the content created while in school will lead to a long career as an independent producer. FrogFish will use both private investment and crowdsourcing to raise capital to continue production after I have left IUPUI. The portfolio I create at IUPUI, the short films and the feature, will be the base I use to fund new projects. And rather than attempt to compete with the flawed Hollywood distribution model, I will increase the opportunity to repay investors through targeted self distribution using ideas and models from other independent filmmakers like Jon Reiss, and friends Eric Anderson, Zack Parker and Joshua Hull, because I believe that in order to have a sustainable career as a filmmaker you have to make money for your investors. However, my goal, and what I hope to achieve after graduation, is to develop a strong fan base that enjoys the stories I like to tell and how I like to tell them.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog then you already know the type of stories I enjoy. You’ve read the original version of the story mentioned in the image, “The Death of Halpin Frayser” and you’ve read my screenplay adaptation. The image is the first panel of the storyboard (which I intend to animate through Photoshop and After Effects…once I get a better handle on them). I am targetting March as the goal for principal photography on the short. I am also still working on the (animated?) graphic novel “The Wet Grave” and have many other projects (like building the website) to complete before graduation. Therefore, while I am blogging today as part of an assignment to discuss what my “dream job” will be when I graduate, I am really trying to remain focused on what I need to accomplish over the next 2-3 months.

And seriously, I do respond to comments. I’d love to hear your thoughts on anything I’ve discussed (particularly if you’ve read Jon Reiss’s book)

Related articles

- NewFilmmakers LA Announces Lineup for November Festival (prweb.com)

- “Engineer the future now. Damn tomorrow, future now! Throw the switches. Prime the charge. Yesterday’s for mice and gods.” (frogfishmedia.wordpress.com)

- IUPUI’s big strides on the nano scale (nuvo.net)

The Mezzotint

M.R. James may be considered the father of the modern ghost story. He abandoned Gothic horror for more realistic contemporary settings. According to his wikipedia page, the classic Jamesian tale consists of:

- a characterful setting in an English village, seaside town or country estate; an ancient town in France, Denmark or Sweden; or a venerable abbey or university

- a nondescript and rather naive gentleman-scholar as protagonist (often of a reserved nature)

- the discovery of an old book or other antiquarian object that somehow unlocks, calls down the wrath, or at least attracts the unwelcome attention of a supernatural menace, usually from beyond the grave.

His story “The Mezzotint” seems to have had a direct influence on Stephen King’s “The Road Virus Head North.” Of his stories that I have read, this one is perhaps my favorite. It is a great read for Halloween and sure to entertain. Be sure to leave a comment below and let me know what you think. I’d love to hear suggestions on other classic horror stories you’d like to read here.

The Mezzotint

by M.R. James

from The collected ghost stories of M.R. James

Edward Arnold & Co., (1931, 1944 ed.)

This story was originally published in 1904.

SOME time ago I believe I had the pleasure of telling you the story of an adventure which happened to a friend of mine by the name of Dennistoun, during his pursuit of objects of art for the museum at Cambridge.